Science for

Sustainable

Agriculture

Could a revival of the UK oilseed rape crop be under way?

James Warner & Julian Little

October 2025

Science for Sustainable Agriculture

According to Defra figures, the 2025 arable harvest was the second lowest on record, with yields hit by heatwaves and drought. But the oilseed rape crop bucked the trend, recording average yields up 29% on 2024 after more than a decade of decline following the withdrawal of neonicotinoid seed treatments, a critical line of defence against the devastating cabbage stem flea beetle (CSFB). The 2024/25 season saw lower pest pressure, but it also coincided with a co-ordinated, cross-sector knowledge exchange push to ‘reboot’ the crop by getting the latest agronomic research and best practice advice into the hands of growers and their advisers. James Warner, managing director of United Oilseeds, and Dr Julian Little, co-ordinator of the OSR Reboot campaign, review the progress and objectives of this industry-led initiative. Does it mark a revival of this iconic break crop, and could there be lessons to be learned from this detail-oriented approach for other crops struggling to realise their yield potential?

In the mid-2010s, oilseed rape was a relatively easy crop to grow. Seed was drilled in late August or early September, and there were relatively few interventions, compared to other crops such as wheat or barley, until preparations for harvest in the July. Whilst, as with most crops, pigeons and slugs posed (and still pose) a problem for oilseed rape, the key pest, cabbage stem flea beetle, both in its adult form as the crop emerged, and its larval stage in the spring, was controlled with the use of neonicotinoid seed treatments such as imidacloprid, clothianidin and thiamethoxam.

The crop area and yields continued to grow to the point that the UK not only satisfied the UK’s edible oil consumption demands for rapeseed oil, but became the fifth largest exporter of oilseed rape, with around 0.75 million tonnes leaving the country.

And then regulatory approval for the use of neonicotinoids in oilseed rape was withdrawn.

What followed was a collapse in the domestic production of oilseed rape; from a high of 750,000 hectares in 2012, there followed a downward trend as farmers lost confidence in being able to bring a crop to harvest, until the 2024/25 season when only just over 200,000 hectares was grown. The UK had gone from a net exporter of oilseeds to a huge importer of the commodity, a (net trade) swing that now costs the UK economy £1 billion each year.

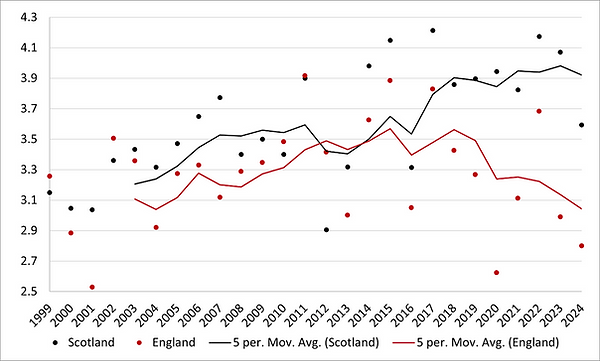

Only in Scotland, where CSFB is not so prevalent, were yields able to make growing the crop viable (see figure below).

Oilseed Rape Yields in Scotland and England

And then came a national campaign which aimed to turn things around for this important home-grown crop. In early 2024, this coordinated effort, named OSR Reboot and initiated by United Oilseeds, explored ways to reinvigorate confidence in growing this crop. Following an open letter to members and the wider industry, a virtual meeting of organisations across the supply chain was convened. Nearly 60 attendees from over 40 different organisations, including farmers and agronomists, cooperatives and trade associations, input providers and distributors, academic researchers and seed breeders, beekeepers and bee farmers, the oil crushers and grain handlers, met with the objective of understanding and then addressing the question of how to sustainably grow a crop of oilseed rape in the absence of an effective insecticide for CSFB control.

After the initial meeting, the group increased its breadth to include Defra, food processors and a large food retailer, and focused on the agronomy, research and potential policy initiatives that might make a difference.

Four objectives were identified:

-

To restore UK OSR self-sufficiency

-

To boost economic growth along the supply chain

-

To provide pollen and nectar supplies to boost biodiversity

-

To address policy inconsistencies to provide a level playing field for UK farmers

What was startling to many was that while much of the research into integrated pest management practices for CSFB control had already been initiated, the results of this research had failed to reach the farmers and the agronomists advising them. Some of the steps involved, such as reiterating the need to shift drilling dates from traditional thinking, the critical need for moisture in the soil, and light cultivation post-harvest in an attempt to disrupt the emergence and migration of CSFB, were immediately implemented for the 2024/25 growing season together with measures to monitor CSFB numbers in the autumn and spring.

To this has been added a further raft of CSFB management strategies, and a research programme partially funded by industry to identify which strategies are “critical” and which are less so, with knowledge transfer pathways embedded as a prerequisite necessity.

And so to the 2024/25 season: the numbers of CSFB were “inexplicably low” and the establishment of the crop excellent, to the point where, despite a sharp reduction in the area of crop grown, production at harvest was up by over 200,000 tonnes compared to earlier estimates due to a near average record yield of 3.9 tonnes/hectare. This equated to an extra £100 million productivity gain for UK plc plus the increase in transport and levy payer money for research. And critically it has increased confidence among farmers that oilseed rape is worth looking at again.

Similarly, the 2025/26 season has started with low CSFB numbers and establishment of the crop, planted on a much wider area, has been good.

It is impossible to gauge the precise reason for these two years of apparent better times for OSR production in the UK. Perhaps different weather conditions or something about the lifecycle of CSFB that we have yet to uncover? Or perhaps the result of a concerted campaign that combines all parts of the supply chain from research to agronomy to policy and, critically, with knowledge exchange between those who have it and those who need it, built in.

Could a similar, detail-orientated approach also help to close a widening yield gap in other arable crops?

Whatever the reason, a sustainable revival of oilseed rape in the British countryside could be underway, with potential benefits for growers, the environment and the UK economy.

James Warner is the Managing Director of United Oilseeds, an independent farmer-owned co-operative, representing 4,500 farmer members' businesses, and the UK's leading break crop specialist founded over half a century ago. James was previously with ADM Agriculture, where he managed the imported sunflower seed meal and rapeseed meal business across the UK and French markets. With over 20 years’ experience in the agricultural sector, his career has included senior international trading and risk management roles with ADM International in Switzerland, where he specialised in rapeseed oil, gas, power, and carbon credit markets. Earlier in his career, James worked as a Rapeseed Crush Trader at ADM Erith, as a Market Analyst with the International Grains Council, and spent seven years in mobile seed processing with Anglia Grain Services.

A Fellow of the Royal Society of Biology, Dr Julian Little has worked in plant science and food production for over thirty years. He holds a first degree in biochemistry and a PhD in molecular plant pathology. After a successful career in a number of crop protection and seed companies, he now helps a range of individuals and organisations improve their communications and public affairs activities in relation to scientific research and innovation in agriculture. He is currently the coordinator of the OSR Reboot Campaign, and is a member of the Science for Sustainable Agriculture advisory group.